Last year, IIM-Ahmedabad did a detailed study comparing the salary and emoluments of employees belonging to government and private sector. The study, commissioned and later factored in by the 7th Central Pay Commission (CPC), took a wide range of samples — doctors, engineers and accounts officers at higher levels, down to the lower skilled categories like electricians, plumbers and drivers. The 291-page study made two straightforward conclusions.

First, the government pays much more than the private sector does as far as low-skilled segments are concerned. Second, government salary is lower in the officers’ segment than in the private sector, particularly in later years of the job.

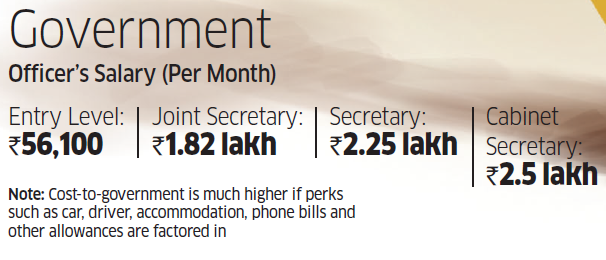

After the CPC’s recommendations were accepted by the government last week, the salary gap between a low-skilled employee in the government and private sector has widened further. The salary of a newly recruited government driver, for instance, is now Rs 18,000 per month, more than double the prevailing market rate. At the officer’s level, the starting monthly salary is Rs 58,100.

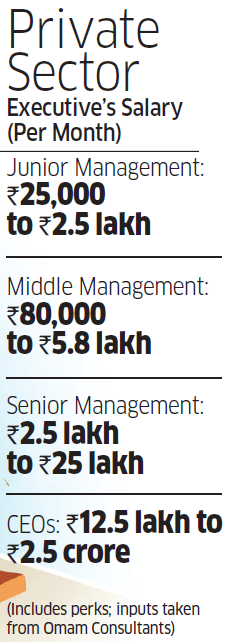

Yes, if compared with a private sector CEO’s salary which ranges between Rs 12.5 lakh and Rs 2.5 crore per month — according to data available with HR consulting firm Omam Consultants — the salary of the cabinet secretary seems paltry; the topmost bureaucrat in the country takes home Rs 2.5 lakh per month. But then, you can’t ignore the embellishments — the tangible and non-tangible perks doled out to a government officer.

Sample this. A Central government officer gets accommodation in Lutyens’ Delhi — the market value of the rent of the cabinet secretary’s bungalow on 32 Prithviraj Road, for example, is several times more than his salary.

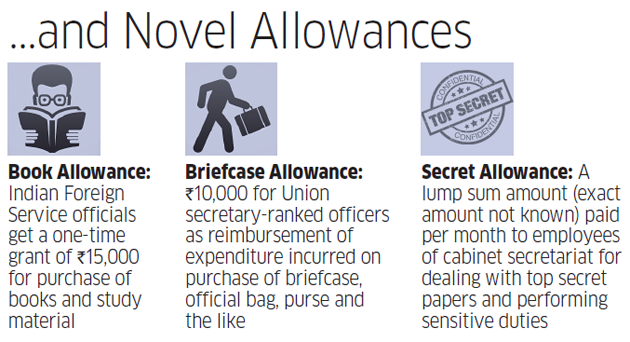

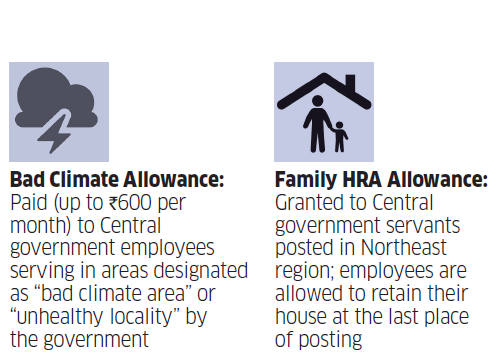

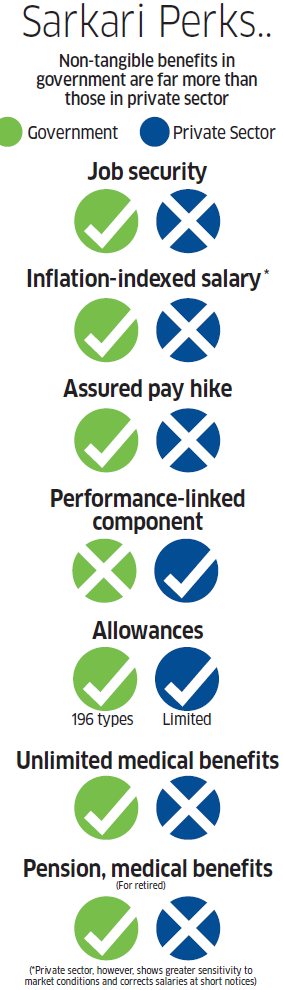

An officer also gets a car, a driver, phone bill reimbursements, unlimited medical benefits for self and dependents, pension and a whole range of allowances, including one-time book allowance for Indian Foreign Service officers, and then a secret allowance — an undisclosed amount paid to officers working in the cabinet secretariat for dealing with top secret papers and performing sensitive duties.

In fact, many of the 196 allowances that exist in the government were not known publicly till Justice (retired) AK Mathur-headed pay panel placed each one of those in public domain and recommended the abolition of 52 such allowances, something that the government has not given a go-ahead as yet, and instead referred the matter to another panel.

And then there are non-tangibles — from job security and prestige to clout (read beacon) associated with the job, something that can’t be measured in monetary value.

Work Satisfaction

Union finance secretary Ashok Lavasa acknowledges that compensation for government employees has gone up considerably, thanks to the liberal approach of the last two pay commissions; the recommendations of the 6th CPC were implemented retrospectively from January 1, 2006.

He reckons that this may explain why the number of government officers who resigned and moved to the private sector has gone down in recent years, though there are no ready statistics to back this.

“Government offers you an amazing range of responsibilities and opportunities to work in public interest. Those who want to move out to the private sector, I think, are attracted by another set of challenges — the private sector has risks but a lot of rewards too,” points out Lavasa, adding that domain experts from the private sector often join the government for reasons other than salary.

Amitabh Kant, Lavasa’s colleague in bureaucracy and CEO of NITI Aayog, argues that no government servant can now be dissatisfied with her pay package after the government decides to implement the 7th CPC in totality. He says it is the job content in the government, and not the salary at all, which attracts young people to join the civil services.

“I could have joined a private company. But I knew I would not get any satisfaction by selling toothpaste,” says Kant, a bureaucrat often credited with driving some major campaigns such as God’s Own Country, Incredible India and Make in India. Kant joined IAS in 1980 but is now serving in NITI Aayog on a two-year contract after his retirement in February this year.

Human resources consultants who ET Magazine spoke to are broadly in agreement with the findings of the IIM-Ahmedabad study. But it’s not all black and white.

For instance, after the 7th CPC, salaries in government have an edge over the private sector, at least in the first 10 years of experience. Although remuneration in the private sector is still more attractive at senior levels, the 7th CPC has perhaps made the task of wooing talent from government even more difficult.

Note: 7th Central Pay Commission recommends abolition of 52 of 196 allowances, but the government has decided to continue all allowances till a newly constituted panel decides on the allowances in the next four months

“Post 7th Pay Commission, it will be difficult for the private sector to attract talent from the government.

Usually, when hiring a government servant, factors such as job security, work-lifebalance, a five-day week, post-retirement benefits and the like that a government servant enjoys are measured and compensated for. Doing that will now become more difficult, thanks to the higher salary base of government servants,” says Anil Koul, director, Omam Consultants.

Performance Analysers

But should the government continue with the practice of an across-the-board salary hike for government servants without factoring in the basics — accountability and performance?

But should the government continue with the practice of an across-the-board salary hike for government servants without factoring in the basics — accountability and performance?

The UPA II government (2009-14) created a performance mechanism called Results-Framework Documents or RFD by setting targets for various ministries and departments, but it became just another cosmetic management tool since almost all the government ministries and departments scored an outstanding ranking.

Also, the mechanism does not solve the basic problem — a low-performing officer getting the same salary as a high-performing one. The current government too continues with the performance management department within the cabinet secretariat, but there is no sign of creating a mechanism of differential pay for different performances.

As Manish Sabharwal, chairman of recruitment firm TeamLease, puts it bluntly, the current pay system in government does not distinguish between a ghoda (horse) and a gadha (donkey). (See “Across-the-Board Pay Commissions….”)

“It is time to bring disruption by instituting a risk-reward-led compensation system that incentivises government employees for thinking out of the box, daring to try new things and delivering high performance. We need to eliminate the system of time-bound raises and allow actual remuneration to be high for the deserving while not impacting the long-term pension burden of the government,” says Aman Kumar Singh, principal secretary to the CM of Chhattisgarh (see “CPC is Good for 80% of Officers, Not 20% of Doers”).

Till the next CPC — possibly in 2024 — the amblers and the drifters will continue to hitch on to the few who choose to gallop. For now, though, the good news for the government is that private sector corporations looking to poach its officers may have to, well, hold their horses.

If a government officer wants the salary of a private sector CEO, my advice is quit your job: Amitabh Kant, CEO, Niti Aayog

On the reasons for young professionals joining government

Young people sit for the civil services examination because of their passion and commitment to make a difference to the nation. They want to join the government for its job content. Many MBAs, engineers and doctors do join the government. I never think they join for a good salary.

On life after the 7th Pay Commission

After the 7th Central Pay Commission is implemented, government salaries will rise to a reasonable level. Now, government officers receive decent enough money to have a good life and to educate their children. A house and a car are given to officers. You can’t expect more. And if a government officer wants the salary of a privatesector CEO, my advice is: quit the job. The government is the wrong place for you.

On his own experience in government

I could have joined a private company. But I knew I would not get any satisfaction by selling toothpaste. The work in the government has given me job satisfaction. At a young age, I could build an airport in Kerala (Kant structured the Kozhikode airport as a private-sector project). I could bring technology to the fisherfolk community of Kerala. If you take into consideration the size and scale of some of the government projects that I handled — whether it’s God’s Own Country or Incredible India, or Startup India — I would not have got the same opportunity in the private sector.

Across-the-board Pay Commissions treat gadha and ghoda equally: Manish Sabharwal

A study by XLRI estimated that the total cost-to-government (CTG) for every government employee was 3.75 times the salary because of benefits that were not monetised. A survey of government servant and service satisfaction among citizens suggested that 85% of them were unhappy with performance. All these data suggest that the 7th Pay Commission should be the last Pay Commission; no organisation should review compensation without a review of performance.

The agenda for the next Central Government Performance or Governance Commission is wide and deep. It must reduce the number of Central government departments by abolishing useless ones and accelerating the transfer of funds, functions and functionaries to state governments. It must introduce the colonel threshold of the Indian Army where if you are not shortlisted for promotion beyond a certain level you retire early. It must monetise all benefits like housing, car and phone, and move to a CTG concept.

It must benchmark CTG to private sector CTC for comparable positions. It must introduce 25% lateral entry on fixed-term contracts after the level of joint secretary. It must reduce the physical and spiritual distance from normal people — like red lights/stars/flags on cars, off-book, government-paid servants at home, excessive security and other drama which corrode state legitimacy. It must separate the regulator, shareholder and policymaker roles in all areas and shift all PSU ownership out of line ministries to a holding company tasked with improving returns, human capital and governance. Most importantly, it must create a transparent performance management system that shifts the criterion from the date of joining for increments and promotions.

Three things are clear. Firstly, India’s labour markets, distorted by people at the bottom of the government, get paid too much and people at the top get paid too little. Secondly, an across-the-board pay commission treats gadha (donkey) and ghoda (horse) equally; we need sharper differentiation because the current system treats our best bureaucrats badly. Finally, individuals operate within a broader ecosystem and we need to reboot government structures, cultures, processes, and incentives to create a fear of falling and hope of rising.

(The writer is chairman, TeamLease)

CPC is good for 80% of officers, not 20% of doers: Aman Kumar Singh

Bureaucracy always evokes strong and diverse emotions, from outright disapproval, denunciation, derision, insouciance and jealousy to vast admiration. These multiply hundredfold when the Central Pay Commission (CPC) is played out like the ritualistic Kumbh Mela with the inevitability of ballyhoos that generate more heat than light. It’s often alleged that the government doesn’t work but ironically everyone wants to work for the government. We must ask ourselves why do “23 lakh people apply for 368 peon posts in UP” (ET, September 16, 2015)? The lowest entry-level job in the government comes with a salary of Rs 20,000 a month with barely hidden perks. Why did thousands of postgraduates, including 23 PhDs, apply for that job? In one phrase: job security.

Therein lies the first uncomfortable truth. At the entry level the government does pay a lot more than the private sector. A typical entrylevel job in a multinational BPO pays Rs 8,000 per month and comes with the risk of layoff; whereas competence is no criterion once past the post in the government. Comparable salary graphs of government and private-sector employees meet and start diverging again near the 10-12-year mark in their careers. For less skilled workers, the government is a better employer. This has led to a “crowding in” of unskilled labour in government.

Also, unwittingly, government becomes less rewarding for highly skilled people. A single-point entry, which ensures a safe, secure and cosy 35-year tenure, coupled with pension on retirement is an idea as obsolete as the typewriter. For every successful senior executive whose salaries make the headlines of the pink papers, there are many whose careers stagnate in middle management. Never in the government, though, where selection for most bureaucrats is not a journey but a destination itself — nirvana. The second truth is more hurtful. In the bureaucracy, Pareto’s Law holds: 20% of the officers are the thinkers and doers carrying the weight of the remaining 80%.

However, the compensation system does not separate the wheat from the chaff. This is the biggest bane of the present system with no performance-linked incentives. The third uncomfortable truth: All the seven CPCs have tried to address this issue but unfortunately the financial part has buried the recommendations on measures to promote efficiency, productivity and economy in government in a heap. Government employees are the only ones who demand and get a raise as a matter of right rather than fiscal ability of employer. There are certain loss-making PSUs and state electricity boards which dole out bonuses every year.

It is time to bring disruption by instituting a risk-reward-led compensation system which incentivises government employees for thinking out of the box and delivering high performance. We need to allow actual remuneration to be high for the deserving while not impacting the long-term pension burden of the government.

This will have a direct impact on the overall efficiency and effectiveness of the government administrative machinery. Compensation of the performers will become commensurate with their efforts and delivery; it will end bureaucratic dysfunction by motivating those who are capable of higher performance but shy away from risktaking, to step up their contribution; also attracting people of high calibre into government service as a natural career choice.

Here, a lesson needs to be drawn from the judiciary, which absorbs the most brilliant from the bar directly to the apex court. One can be a Supreme Court judge in early 50s but a secretary to GoI only in late 50s. This deprives government of the benefit of service of the most eligible bureaucrats and specialists.

Most bureaucracies around the world suffer from a time-bound approach to remuneration, but some countries have successfully tried a different route. Hungary uses a system of payment by results. It not only rewards performance but also penalises for lack of results. Spain uses a collective performance system where departments are evaluated against clear productivity goals set every year. Singapore and Germany use a system of goal setting that is done centrally, while the US has a system of setting goals by individual agencies themselves.

Pay commission means different things to different people. If one is in the 80% category, piggybacking on the 20% performers, the 7th CPC recommendations are good news, a feeling perhaps not shared by the slogging 20%. We want better and brighter people in government not because it offers lifetime employment guarantee but because it offers the satisfaction of making a difference in the lives of the common man while getting suitably rewarded for it. Unless this systemic malaise is addressed, CPC would be criticised as boondoggle.

Bureaucracy today is at an inflection point and faces unprecedented headwinds. It’s time for the pooh-bahs to wake up and smell the coffee. A mix of smarter politicians, RTI and social media now ensure that it is a system weakening at its roots. A slack bureaucracy can no longer kick the can down the road as it is fast running out of road.

Source:- Economics Times

CommentsComment